Scientists See Supernova in Action

Scientists See Supernova in Action

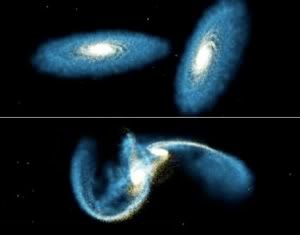

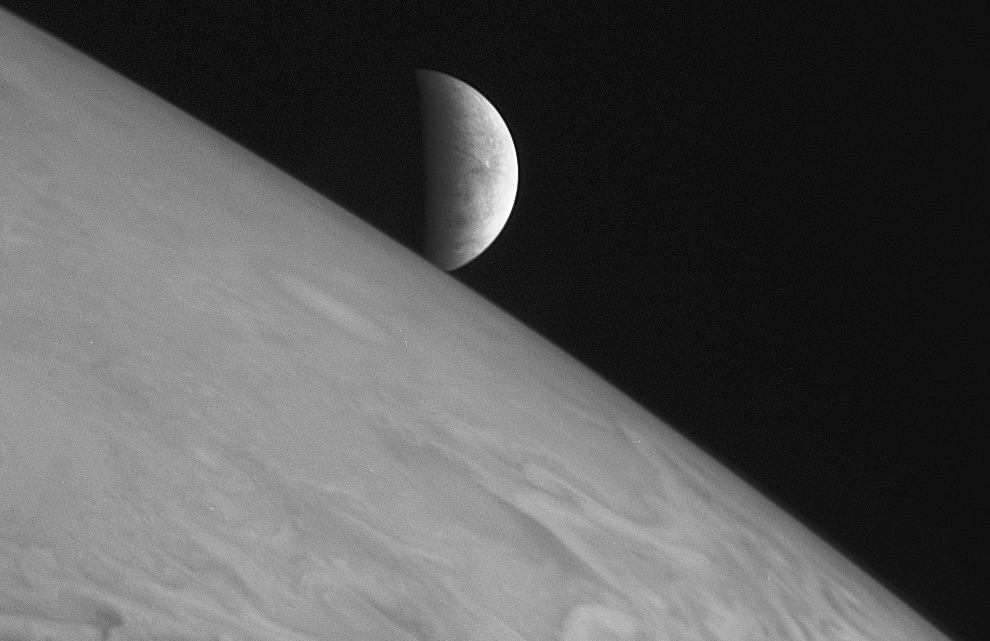

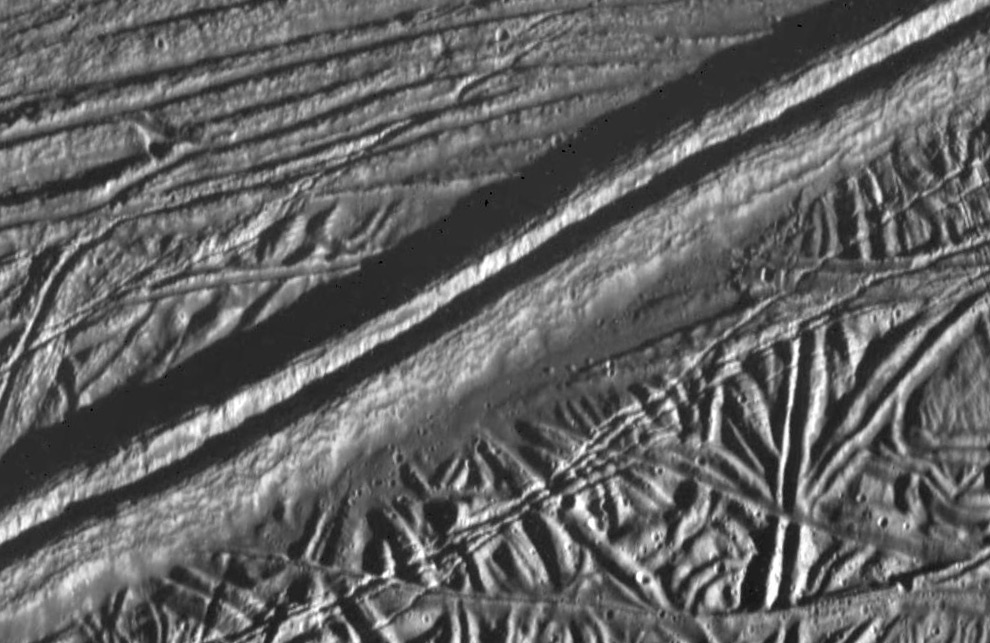

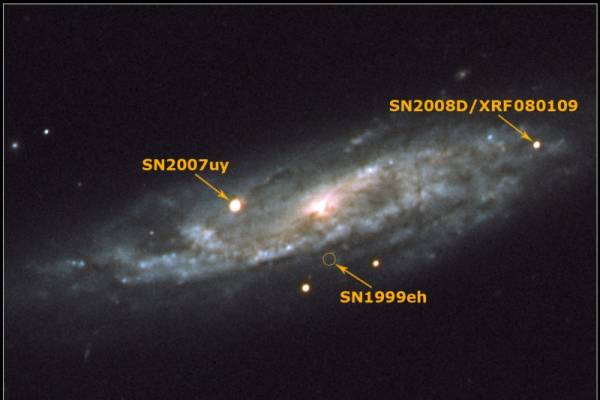

Supernova 2007uy in the galaxy NGC2770 was already several weeks old on January 7, 2008 when NASA's Swift satellite took the image at left.

The image on the right was taken two days later and shows Supernova 2008D as well.

Astronomers witnessing the birth of an exploding star for the first time have seen a burst of X-rays as the star disintegrates.

Image: Supernova SN2008D.

A star trembled on the brink of eternity.

Outwardly all was serene, but its inside was falling into chaos.

Far away on the day of Jan. 9, Earth time, a satellite telescope by the name of Swift, which happened to be gazing at the star”s galaxy, a smudge of stars 88 million light-years away in the constellation Lynx, recorded an unexpected burst of invisible X-rays 100 billion times as bright as the Sun.

Alicia Soderberg, a Princeton astronomer who had been using the NASA satellite to study the fading remains of a previous supernova explosion, received the startling results of that observation by e-mail while giving a talk in Michigan.

Recognizing that this was something extraordinary, she sounded a worldwide alert.

In the following hours and days, as most of the big telescopes on Earth, and the Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-ray Observatory watched from space, the star erupted into cataclysmic explosion known as a supernova, lighting up its galaxy and delighting astronomers who had never been able to catch an exploding star before it exploded.

“We caught the whole thing on tape, so to speak,” Dr. Soderberg said in an interview.

“I truly won the astronomy lottery. A star in the galaxy exploded right in front of my eyes.”

She and 42 colleagues from around the world have now told the tale of this discovery in a paper in Nature to be published Thursday and in a telephone news conference Wednesday.

The observations, they say, provide a new window into the process by which the most massive stars end their lives and give astronomers new clues on how to look for these rare events and catch them while they are still in their most explosive, formative stages.

”Most supernovas,” Dr. Soderberg explained, “are discovered and classified by their visible light, but that typically does not happen until theexplosion is a month or more old and has brightened enough to be seen over intergalactic distances.”

The true fireworks, she said, happen much earlier when a shock wave from the imploding core hits the star’s surface, producing so-called breakout light, which lasts only a few minutes.

“The physics of the explosion is encoded in the breakout light,” Dr. Soderberg said, adding that the chance that the Swift telescope was observing during those moments was “unfathomable.”

Astronomers now know, however, that X-rays from the breakout can be an early alert. “Supernova 2008D was the first to be found from its X-ray emission,” said Robert Kirshner, a supernova expert at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, referring to the supernova by its official name, “but if we build the right type of X-ray satellites, it won”t be the last supernova we find this way.”

“That is really what is so wonderful here,” he said.

”So new were the X-rays,” said Dr. Soderberg, “that she and her collaborators did not know they were looking at an incipient supernova until a day or two later and ground-based telescopes had seen it grow in visible light.”

“It was a baby supernova in that sense,” Dr. Soderberg said.

“Here was an object brand new. At first we didn”t recognize it.”

The supernova was of a sort known as Type Ibc, the rarest and most luminous of the explosions caused by the collapse of the cores of massive stars, theastronomers have concluded.

Another kind, known as Type Ia supernovas, are believed to result from the destruction of much smaller stars and are beloved of cosmologists who use them to track the expansion of the universe and effects of dark energy.

The star that died last January could have been 20 times as massive as the Sun or even bigger, Dr. Soderberg said.

It was probably a type called a Wolf-Rayet star.

They are very hot stars with surface temperatures of 50,000 degrees Fahrenheit or more and are often blowing gas away in strong winds. Dr. Soderberg described them as “very violent stars, very massive.”

Because it is gravity that stokes the thermonuclear furnace at the centers of stars, the more massive they are, the younger they die.

In the case of a star 10 or 20 times as massive as the Sun, it could be only a few million years. “These stars live fast and die young.

We don”t know if they leave a beautiful corpse,” Dr. Kirshner said.

Many of the elements necessary for life and its accessories, like carbon, oxygen, iron and gold, are produced in a thermonuclear frenzy during the final stages of these explosions, which then fling them into space to be incorporated into new stars, new planets, new creatures.

“If you”re wearing gold jewelry,” Dr. Kirshner said, “it came from a supernova explosion.”